When we started www.KnowYourCharter.com, some criticized us for only posting district and charter school data. They said the only "fair" comparison (even though it is districts that lose money from the charter school funding system, not schools) was to look at building-to-building data. We chose to look at district-level data first because it is districts, not individual schools in them, that lose money to charters.

Well, today we posted the building data as well. So now it is possible to compare every Ohio school building -- district or charter -- with each other, as well as districts. This adds to the comparative data available at Know Your Charter. Including the building level data increases by 17 the number of data points now available for the public to compare. Adding those 17 points to the 26 from the original site and there are now 43 data points for comparing districts, schools and charters.

Can we finally stop claiming Know Your Charter isn't fair? Everything is there for all to see. And what you'll see is that urban buildings more than hold their own with charter schools overall -- outperforming them on proficiency tests while having higher levels of poverty. You'll also see that less than 10% of charter school children are in buildings that outperform urban districts. Overall, urban buildings do better than charters, with a few exceptions in Cleveland and other places.

The time has come to stop debating whether the Ohio charter school program is working. It clearly isn't in the vast majority of cases. It's up to the state to figure out how to make it work better for the kids in the charters without unduly hampering the educational opportunities for the 90% of Ohio children in local public schools.

I've never been more encouraged that we'll see that happen than this year. But we must not let up on the pressure to make necessary changes. Our kids need us to do this.

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Tuesday, February 10, 2015

Kasich's Frankenstein Complex

In today's Columbus Dispatch, Gov. John Kasich came out attacking those who call his school funding plan "Robin Hood" -- a pretty clear response to sentiments captured in an Akron Beacon Journal story this morning.

He said that "we need more superintendents who are educators and fewer who are politicians."

What Kasich forgets is the reason Ohio superintendents have had to become politicians -- because more than 1/2 of school districts will have less state money in his current budget than they had six years ago.

That forces districts to ask for levy money. Levies are political campaigns. So, yes, superintendents have to be more political because they have to win elections every few years to provide the education their kids deserve and the state won't pay for.

Like Frankenstein, Kasich has declared war on a monster of his own creation. Unlike Frankenstein, he is in denial of his handiwork.

Noticeably absent from Kasich's anger is any mention of the real Ohio "educator politicians" -- poor performing charter school operators. This state has seen $1.7 billion going to two big campaign contributors (more than $6 million at last count) who run mostly failing charter schools -- one out of every four charter school dollars ever spent here.

I doubt superintendents have given even $10,000 total over the last 16 years to state politicians, let alone the $6 million plus that just two charter school operators have.

If Kasich wants superintendents to not think like politicians, he needs to provide state funding increases in more than 45% of school districts compared with 6 years ago, even though he has $20 billion more to spend.

If he did that, superintendents would have to worry less about passing levies and could actually be that which they trained to be -- educational leaders.

He said that "we need more superintendents who are educators and fewer who are politicians."

What Kasich forgets is the reason Ohio superintendents have had to become politicians -- because more than 1/2 of school districts will have less state money in his current budget than they had six years ago.

That forces districts to ask for levy money. Levies are political campaigns. So, yes, superintendents have to be more political because they have to win elections every few years to provide the education their kids deserve and the state won't pay for.

Like Frankenstein, Kasich has declared war on a monster of his own creation. Unlike Frankenstein, he is in denial of his handiwork.

Noticeably absent from Kasich's anger is any mention of the real Ohio "educator politicians" -- poor performing charter school operators. This state has seen $1.7 billion going to two big campaign contributors (more than $6 million at last count) who run mostly failing charter schools -- one out of every four charter school dollars ever spent here.

I doubt superintendents have given even $10,000 total over the last 16 years to state politicians, let alone the $6 million plus that just two charter school operators have.

If Kasich wants superintendents to not think like politicians, he needs to provide state funding increases in more than 45% of school districts compared with 6 years ago, even though he has $20 billion more to spend.

If he did that, superintendents would have to worry less about passing levies and could actually be that which they trained to be -- educational leaders.

Thursday, February 5, 2015

Kasich Charter School Reforms Ignore Charter Schools

Ohio has has a major charter school problem for years now. Recently, many have said change is needed, including Gov. John Kasich. He made the statement two months ago that "we are going to fix the lack of regulation of charter schools."

Then he introduced a plan that goes after charter school sponsors, which are not, in fact, schools. That's helpful, but it's still relying on charter school sponsors that have done a lousy job regulating their charters for more than 15 years now. I'm not entirely certain that relying on sponsors some more will change things. I'm more concerned about the buildings in which kids are learning, or too frequently in this state, not learning.

I hesitate to write anything about Kasich's plan because the last time he introduced some school ideas, the written legislation differed vastly from the rhetoric. But let's look at what he's proposing and see how it's going to address the two major issues with Ohio's charter school law -- too many bad ones keep operating for too long, and the funding system leaves the 90% of kids not in charters with significantly less state revenue, forcing local taxpayers to subsidize the state payments to what are in the vast majority of cases poorer performing charter schools.

I have taken these provisions from the Plain Dealer story about them from earlier this week. Again, strong caveat: The bill language may differ greatly from these outlined provisions.

Here are my key points to any meaningful charter school reform, in no particular order:

Then he introduced a plan that goes after charter school sponsors, which are not, in fact, schools. That's helpful, but it's still relying on charter school sponsors that have done a lousy job regulating their charters for more than 15 years now. I'm not entirely certain that relying on sponsors some more will change things. I'm more concerned about the buildings in which kids are learning, or too frequently in this state, not learning.

I hesitate to write anything about Kasich's plan because the last time he introduced some school ideas, the written legislation differed vastly from the rhetoric. But let's look at what he's proposing and see how it's going to address the two major issues with Ohio's charter school law -- too many bad ones keep operating for too long, and the funding system leaves the 90% of kids not in charters with significantly less state revenue, forcing local taxpayers to subsidize the state payments to what are in the vast majority of cases poorer performing charter schools.

I have taken these provisions from the Plain Dealer story about them from earlier this week. Again, strong caveat: The bill language may differ greatly from these outlined provisions.

- Sponsors can be shut down if they score “poor” – a subsection of the current “ineffective” category.

- This could be fine, but it remains to be seen how many sponsors this will actually roll up. It could just snip off a sliver of the smaller, weaker sponsors that don't have that many schools anyway. The more schools you have, the more protection you'd have. And it's the big sponsors that have caused many of the issues here.

- Sponsors rated as "ineffective" have a year to improve, or their sponsorships will be shut down.

- This would help strengthen the previous section. But it still gives the huge bad apples one year to drop their bad schools so they can stay open. Without a provision addressing sponsor hopping, those bad charters can then be picked up elsewhere. So it's difficult to say how effective this will be.

- Charter schools sponsored by an "exemplary" sponsor can seek a property tax levy from voters to pay for operations, which has to be put on by the local school district.

- Wow does this open up a can of worms. Why politicians who support charter schools and choice in general won't create new funds to pay for them is beyond me. I can't envision a school board allowing any charter to seek a levy, the relationship has been so politically poisoned from nearly 20 years of distrust.

- And, again, this is based on a sponsor's rating, not the charter seeking the levy. So we could have a charter that gets a bunch of Fs on the report card getting local levy money because they're in with a big sponsor whose rating isn't as impacted by their failings.

- And as I've written earlier, how would this work? It would allow groups of charters to go for local levy money too. How would that work? Would, for example, Akron property taxpayers fund charters in Xenia (Summit Academy runs schools in both places)? And will charters have the local money "charged off" against their state money, like districts do? A lot of work needs to be done on this to figure it out.

- The state creates a $25 million fund to help charter schools purchase or renovate facilities, but only if the charter is sponsored by an "exemplary" agency. Not to online schools. ODE and the Ohio Facilities Construction Commission develop guidelines for the fund.

- Again, this focuses on the sponsor, not the charter. So you could, theoretically, have poorer performing charters getting a big boost in funding because they're in with a huge sponsor whose rating isn't as harmed by their presence.

- The idea of capital money for charters has merit because many end up with ne'er-do-well operators because the operators have money for their buildings. I like the idea of a separate fund for this purpose, rather than creating more headaches going through the Ohio School Facilities Commission.

- Every sponsor must be approved by ODE and go through the state review and rating process. This would apply even to school districts that sponsor charter schools within their districts. If a district doesn't meet sponsorship standards, the state won't let it create a charter. This new rule would eliminate the exemption for original sponsors.

- This is probably the strongest reform among the lot. Granting ODE more regulatory authority over sponsors is a big step. No question. Will the review be rigorous? Will the hammer be big enough to shut down the big sponsors that have turned blind eyes to charter failures for 15 years? That remains to be seen. But giving ODE -- a public entity -- more regulatory authority over the mostly private entities running charter schools is a good step toward accountability and transparency over the $900 million plus in taxpayer money going to charters. And having it apply to the formerly grandfathered charter sponsors is a huge step. Kudos for that.

- Sponsors cannot sell goods or services to schools they sponsor.

- This is a no-brainer. Which makes the fact it's taken 15 years to have it written into law so infuriating.

- Charter schools would to have their own fiscal agent or treasurer who is independent of a sponsor or the management company running the school.

- Again, a no-brainer. Again infuriated it took 15 years to do this.

- Eliminate the charter operator's ability to appeal their firing by a school.

- Kind of another no-brainer. The school should have latitude in deciding who operates the school. Ohio has been notorious for operators deciding who's going to be on the charter school board. This should help break that cycle.

- ODE has tougher rules for sponsorship.

- For years, ODE has had very little authority to deny sponsors or charters from running. Granting them better regulatory oversight is essential in any reform package. Just how strong the authority will be -- will it be Massachusetts strong? At least? -- is another story.

Here are my key points to any meaningful charter school reform, in no particular order:

- Fund charters based on what it costs the charter to educate the child, not the district.

- Most of the funding problem stems from the fact that charters get paid based on the much higher cost structure of a public school district.

- Direct fund charters from the state, not have it come out of the district's aid.

- This is an idea that all sides have agreed to before. We should do this now.

- Allow high performing charters access to a new state fund that would essentially constitute a local funding amount.

- As we will see during the next several weeks, letting charters go for levies is fraught with issues. The cleanest way to make up a charter's lack of local funding is create a fund at the state level that would provide essentially the same amount as a local levy, but only to charters that are doing a good job, not unlike what Kasich's proposing on capital funding. I'm sad to say this wouldn't cost a lot because there aren't a ton of high performers here.

- Examine a potential cap on the state money going to a charter to something closer to what the district would receive from the state for the child.

- Charters don't get local revenue, so that has to be taken into account. But districts that get $800 a kid from the state shouldn't lose $5,800 from the state if that kid goes to a charter. There's a middle ground that can be struck.

- Allow high performing charter schools to collect capital funding.

- One of the real problems in Ohio is charters have to go to ne'er do well operators to fund their buildings. This would help that problem. The major difference between this idea and Kasich's proposal is it would focus on the quality of the school, not the sponsor.

- Close any charter that hasn't scored in the bottom 5% of school districts on the Performance Index Score. Now.

- This may sound arbitrary, but it has some logic to it. If districts score in the bottom 5% of the Performance Index Score, charters can open up in those districts. Why, then, should charters be allowed to score below that number, if it's such a bad indicator for a district that the state says they need competition and kids need other options?

- Close charters after 3-4 years of failing, not 6-7.

- We've known for a while now that charters are going to be what they are after three years. Let's not let them linger.

- Adopt the national standards for charter school sponsors.

- Codify most of the national charter school authorizer language, then require all sponsors to meet those requirements in the 2016-2017 school year.

- Require all sponsors, schools and operators to adhere to the same open records and meetings laws as any public school and district, including having all their financial records and contracts open for inspection.

- If charters want to be considered public schools, they need to be as open for public inspection as any other public entity.

- Require anyone overseeing, operating or running a charter to file reports with the Ohio Ethics Commission so we can see any potential conflicts of interest.

- Again. No-brainer.

There are other provisions I would like to see, but these are the big ones for me. Will any of them pass this General Assembly? I don't know. But I am grateful that folks on all sides of the aisle are talking about these issues in earnest. We have an opportunity this year to create the country's greatest, strongest, and most publicly accountable charter school system in the country.

So I implore our leaders to show the nation how we can lead on this, our most contentious issue.

What a great opportunity we have before us. Let's not waste it.

Wednesday, February 4, 2015

New Funding Formula's Big Blindspot: Reality

The new school funding formula released Wednesday has some positive things in it. For example, it looks like the poorest districts in the state do better than the wealthier. I take that to mean the formula is woefully inadequate because one shouldn't have to rob Peter to pay Paul; there should be enough for Peter and Paul. But within the confines of an inadequately funded formula, funding those districts that are in greatest need should be prioritized.

However, let's tap the brakes on the "Hooray for Equity" Bus. Because while the governor's formula does take into account a district's "ability to pay" for schools, it leaves out a very important measure -- its actual ability to raise revenue. Instead of looking at what a district actually raises on one mill of property tax, it looks at the district's property valuation and income. Both of those measures have value, but they miss the point.

The reason the Ohio Supreme Court ruled four times that relying too much on property taxes is unconstitutional was because districts that raise small amounts of revenue on a mill have to tax themselves at very high rates, while districts that raise a ton of revenue don't. So the measure that is most grounded in the bottom line -- what can a district contribute -- is more closely related with how much it raises on a mill that it takes to voters, not its overall valuation and income, though those can illuminate the overall picture. The bottom line for me is this: How much would local voters have to raise to replace cuts, and how much don't they have to go for now that they have an increase?

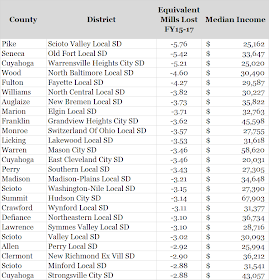

And one can see this issue immediately when you look at what happens in each district under the new runs. Here are the top 25 districts (capacity to raise a mill and median income from latest District Profile Report I have) that have the most equivalent mills removed from their districts under the new formula (total losses in this biennium vs. what they got this school year).

Yes, there are some wealthy districts in there, but the average median income for this group is a bit more than $33,892 -- slightly above the statewide average median of $33,122. Yes, Hudson, Strongsville and Mason are included. But so are Scioto Valley in Pike County and Warrensville Heights. In fact, remove Hudson, Strongsville and Mason and the average median income in the remaining districts is $30,806 -- well below the state average.

What does this mean? It means that many poorer districts will have to ask for significant local levies of their lower income residents to make up the losses from this formula. And that's with the extreme Robin Hooding going on. Again, another instance of explaining why equity means very little if you have inadequate resources to distribute.

Meanwhile, the top 25 increases by equivalent mills are all in districts that have median incomes far below the state average.

As you can see, the redistribution of this formula seems to work better on the handing out of the money rather than the taking of the money. Why would this be?

Simple: Adequacy.

There simply isn't enough state money in the wealthiest districts to provide the funds necessary in the state's poorest areas. That's why places like Scioto and Symmes Valley get caught up in the large relative cuts, as well as the Hudsons and Masons.

What this new formula demonstrates pretty clearly is this: without adequate resources, it is impossible to only take from the state's wealthiest districts and give only to the poorest. In order to provide for the state's poorest districts, you have to take from its middle class and even some poor districts as well.

There is no better demonstration of inadequacy than the two districts that get the most equivalent mills removed and added to their bottom lines. Scioto Valley residents, who make $25,162 have to raise more than 5 mills to replace their cut -- the state's largest loss. Western Local residents, who make a bit less at $24,223 will see the equivalent of 24.8 mills in new state money coming to their district.

What's significant about these two outcomes?

The districts are in the same county and actually share a border. Yet one loses the largest equivalent millage and the other gains the largest equivalent millage.

'Nuff said.

With apologies to Stan Lee.

However, let's tap the brakes on the "Hooray for Equity" Bus. Because while the governor's formula does take into account a district's "ability to pay" for schools, it leaves out a very important measure -- its actual ability to raise revenue. Instead of looking at what a district actually raises on one mill of property tax, it looks at the district's property valuation and income. Both of those measures have value, but they miss the point.

The reason the Ohio Supreme Court ruled four times that relying too much on property taxes is unconstitutional was because districts that raise small amounts of revenue on a mill have to tax themselves at very high rates, while districts that raise a ton of revenue don't. So the measure that is most grounded in the bottom line -- what can a district contribute -- is more closely related with how much it raises on a mill that it takes to voters, not its overall valuation and income, though those can illuminate the overall picture. The bottom line for me is this: How much would local voters have to raise to replace cuts, and how much don't they have to go for now that they have an increase?

And one can see this issue immediately when you look at what happens in each district under the new runs. Here are the top 25 districts (capacity to raise a mill and median income from latest District Profile Report I have) that have the most equivalent mills removed from their districts under the new formula (total losses in this biennium vs. what they got this school year).

Yes, there are some wealthy districts in there, but the average median income for this group is a bit more than $33,892 -- slightly above the statewide average median of $33,122. Yes, Hudson, Strongsville and Mason are included. But so are Scioto Valley in Pike County and Warrensville Heights. In fact, remove Hudson, Strongsville and Mason and the average median income in the remaining districts is $30,806 -- well below the state average.

What does this mean? It means that many poorer districts will have to ask for significant local levies of their lower income residents to make up the losses from this formula. And that's with the extreme Robin Hooding going on. Again, another instance of explaining why equity means very little if you have inadequate resources to distribute.

Meanwhile, the top 25 increases by equivalent mills are all in districts that have median incomes far below the state average.

As you can see, the redistribution of this formula seems to work better on the handing out of the money rather than the taking of the money. Why would this be?

Simple: Adequacy.

There simply isn't enough state money in the wealthiest districts to provide the funds necessary in the state's poorest areas. That's why places like Scioto and Symmes Valley get caught up in the large relative cuts, as well as the Hudsons and Masons.

What this new formula demonstrates pretty clearly is this: without adequate resources, it is impossible to only take from the state's wealthiest districts and give only to the poorest. In order to provide for the state's poorest districts, you have to take from its middle class and even some poor districts as well.

There is no better demonstration of inadequacy than the two districts that get the most equivalent mills removed and added to their bottom lines. Scioto Valley residents, who make $25,162 have to raise more than 5 mills to replace their cut -- the state's largest loss. Western Local residents, who make a bit less at $24,223 will see the equivalent of 24.8 mills in new state money coming to their district.

What's significant about these two outcomes?

The districts are in the same county and actually share a border. Yet one loses the largest equivalent millage and the other gains the largest equivalent millage.

'Nuff said.

With apologies to Stan Lee.

Is Transportation Money Baked into New School Funding Numbers?

In looking at the state's new school funding runs, it appears that once again transportation funds are included in the state aid amounts -- a problem that led to substantial shortfalls for many districts last budget cycle.

In prior budgets, transportation was funded outside the state's operating budget formula. But starting last budget, transportation was included. That, essentially, shorted transportation funding because a district's increase was capped at a certain level. So in many cases, districts would end up receiving less money for transportation than they needed, forcing them to utilize funds from elsewhere to make up the shortfall.

In looking at the state aid figures used to compare the new fiscal year 2016 and 2017 budget, it appears that the same baseline amount is applied in this budget as last one, which would mean that transportation costs are once again rolled into the districts' foundation formula. And gains are once again capped by the state, potentially leaving many districts with short transportation funds. Again

The Governor's office did not give a district-by-district break down of the different components that went into this year's state aid calculation, so it's not entirely clear whether transportation is included in the formula again. However, if it is, and the state decided to increase transportation funding this year, then much of the increase in school funding can be attributed to the increase in transportation funding -- a provision that wasn't even in the formula as recently as three years ago.

Stay tuned.

In prior budgets, transportation was funded outside the state's operating budget formula. But starting last budget, transportation was included. That, essentially, shorted transportation funding because a district's increase was capped at a certain level. So in many cases, districts would end up receiving less money for transportation than they needed, forcing them to utilize funds from elsewhere to make up the shortfall.

In looking at the state aid figures used to compare the new fiscal year 2016 and 2017 budget, it appears that the same baseline amount is applied in this budget as last one, which would mean that transportation costs are once again rolled into the districts' foundation formula. And gains are once again capped by the state, potentially leaving many districts with short transportation funds. Again

The Governor's office did not give a district-by-district break down of the different components that went into this year's state aid calculation, so it's not entirely clear whether transportation is included in the formula again. However, if it is, and the state decided to increase transportation funding this year, then much of the increase in school funding can be attributed to the increase in transportation funding -- a provision that wasn't even in the formula as recently as three years ago.

Stay tuned.

Does Kasich School Funding Plan Dip into Local Revenue?

Gov. John Kasich's released the much anticipated district-by-district runs on his school funding changes. And (as is usually the case with initial runs), it's difficult to compare. That's because the governor's office decideed to tell you whether you got a cut or increase based on your total state and local revenue. Which, of course, hides the massive Robin Hooding that's going on in this latest incarnation of Kasich's school funding plan.

But what's amazing is when you strip away the percentages in the released sheets and look at the percentages in just state aid. When that happens, you see that Beachwood, Mayfield Heights and Cuyahoga Heights lose more money than they received in this school year in state aid, raising a very legitimate question: Is the state essentially dipping into those districts' local tax dollars to pay for this scheme?

This massive cut happens because they lose significant chunks of the reimbursement payments for lost tangible personal property and public utility taxes, but it's still a milestone. This is Robin Hooding of the first order -- a severe redistribution of wealth. What this also shows is how inadequate the overall amount really is. If you have to remove the equivalent of a district's state aid payment (I don't care how wealthy they are) to make the formula work better for the most needy districts, then you don't have enough money in the formula.

This reality is well hidden in the district simulations because the cut and increase percentages are relative to a district's state and local aid -- a column that's never before been used in a state school funding simulation. So while, for example, the governor's runs show that Orange will lose 1.7% of its funding next year, it will really lose 32.3% of its total state aid. Again, the way these sheets have always been used is to compare state to state aid -- apples to apples, if you will.

Kasich's team has tried to bury a very nasty little fact in their simulations -- they are bleeding the funding from wealthy districts to fund less wealthy districts because they don't want to commit enough state money to make their own formula work for everyone. And that's a shame.

But what's amazing is when you strip away the percentages in the released sheets and look at the percentages in just state aid. When that happens, you see that Beachwood, Mayfield Heights and Cuyahoga Heights lose more money than they received in this school year in state aid, raising a very legitimate question: Is the state essentially dipping into those districts' local tax dollars to pay for this scheme?

This massive cut happens because they lose significant chunks of the reimbursement payments for lost tangible personal property and public utility taxes, but it's still a milestone. This is Robin Hooding of the first order -- a severe redistribution of wealth. What this also shows is how inadequate the overall amount really is. If you have to remove the equivalent of a district's state aid payment (I don't care how wealthy they are) to make the formula work better for the most needy districts, then you don't have enough money in the formula.

This reality is well hidden in the district simulations because the cut and increase percentages are relative to a district's state and local aid -- a column that's never before been used in a state school funding simulation. So while, for example, the governor's runs show that Orange will lose 1.7% of its funding next year, it will really lose 32.3% of its total state aid. Again, the way these sheets have always been used is to compare state to state aid -- apples to apples, if you will.

Kasich's team has tried to bury a very nasty little fact in their simulations -- they are bleeding the funding from wealthy districts to fund less wealthy districts because they don't want to commit enough state money to make their own formula work for everyone. And that's a shame.

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Will Charter Schools Get a Charge Off?

I'm sorry to go geek on you, but I have to in order to fully explain the point of this post. In Gov. John Kasich's new biennial budget, he wants to allow charter schools to collect local revenue on top of their state revenue. Just like districts, he argues. So that's fair and equitable, right?

Well, maybe. See, here's the issue. When a district raises local revenue, the state counts that against them on their state money. So if a district can raise, say 50% of the cost of educating kids in their district, the state picks up the other 50%. This elimination of 50% of their state revenue to be filled in by local revenue is what's called a "charge off."

However, it appears that in Kasich's budget proposal, the local revenue charters raise would not be counted against their state money.

So, charter schools would receive all the state money the state says they need (right now, the minimum charter school deduction from school districts is about $1,600 more than what the average Ohio district gets from the state because of this "charge off"), plus local revenue on top of that. Meanwhile, school districts receive significantly less state money than the state says they need with their local revenue making up the difference.

Doesn't sound quite so fair now, does it?

What's ironic is that Ohio's public school advocates have clamored for years for the state to fund them exactly as the charter schools that get local revenue would be funded under Kasich's plan.

If we want charter and traditional school funding to be equitable (as charter advocates have claimed they want), then the state must do one of two things with this new local funding element: eliminate the charge off for districts, or create one for charters.

Any other way seems pretty unfair.

Well, maybe. See, here's the issue. When a district raises local revenue, the state counts that against them on their state money. So if a district can raise, say 50% of the cost of educating kids in their district, the state picks up the other 50%. This elimination of 50% of their state revenue to be filled in by local revenue is what's called a "charge off."

However, it appears that in Kasich's budget proposal, the local revenue charters raise would not be counted against their state money.

So, charter schools would receive all the state money the state says they need (right now, the minimum charter school deduction from school districts is about $1,600 more than what the average Ohio district gets from the state because of this "charge off"), plus local revenue on top of that. Meanwhile, school districts receive significantly less state money than the state says they need with their local revenue making up the difference.

Doesn't sound quite so fair now, does it?

What's ironic is that Ohio's public school advocates have clamored for years for the state to fund them exactly as the charter schools that get local revenue would be funded under Kasich's plan.

If we want charter and traditional school funding to be equitable (as charter advocates have claimed they want), then the state must do one of two things with this new local funding element: eliminate the charge off for districts, or create one for charters.

Any other way seems pretty unfair.

When Equity Isn't Enough

Yesterday, Gov. John Kasich revealed his $72 billion budget (which is more than $20 billion more than the one I handled in 2009, but that's a different story). In it, Kasich calls for changes to the way Ohio's schools receive state revenue. It will lead to some districts getting cuts and others not.

First of all, it's the state whose responsibility it is to provide the funding for education in this state, not local taxpayers. That's what the Ohio Supreme Court ruled four different times. Districts need to ask the state to "step up and help." So that comment was insulting to the Ohio Constitution, not to mention the districts whose communities simply won't pass levies, despite years of trying.

But let's go beyond that and talk about what Kasich means. He's saying, essentially, that if you have the capacity to raise your taxes to pay more for schools than you are, then he's going to cut your state money to punish you. No word if he will then endorse the subsequent levy that will have to go on the ballot to replace that money. But that's the idea. Take money from districts whose taxpayers aren't paying enough and give it to poorer districts whose taxpayers are stepping up more.

The district-by-district runs are not yet out. And what Kasich says and what the runs end up actually doing have diverged quite a bit in recent budgets. But assuming that's the result -- that communities that have contributed more locally will get a bump at the expense of communities that have not, it seems like a push toward equity. And that's good, right? Well, not really.

The effort is meaningless because it's still inadequate.

When you admit that more than 1/2 of all districts will get cut under this plan, even though you're touting a "record" level of funding for schools (a highly dubious claim employing the fuzziest of math), something isn't right. And that something is that the state is not spending enough to properly fund schools.

The fact you are taking money from districts to fund other districts means you don't have enough to fund both. Period. It's inadequate.

And while I love the idea of equity, it doesn't matter if there's an inadequate amount of money to distribute. Here's a demonstration by way of example.

I am taking three of my friends to a $10 movie. I have $36 in my pocket, and no one else has anything. If I equitably distribute the money, we all get $9, but guess what? None of us get into the movie because it's inadequate to meet the ticket price. The only way any of us see the movie is if I decide to inequitably distribute the money so that two or three of us can see it. Maybe it's the two or three who really want to see it, or it's the two or three who help me out the most with babysitting my kids, or it's the two or three who make the least amount of money and can't afford to go without my help. Or I let one friend go without because I know he's got $10 in the console of his car. Whatever the reason, though, I'm pretty well deciding whose worthy of my inadequate amount of money. All of those are perfectly legitimate ways to decide who gets into the movie, but it misses the point.

The essence of true equity is that everyone gets in, regardless of circumstance.

To finish my example, I need to find four more dollars. That's true equity.

What this silly analogy is trying to show that that you simply cannot have true equity without adequacy. This is a concept that Kasich and others simply don't either understand or don't want to face. Because it means that they will have to find a bit more money in the largest state budget of all time for the 1.7 million kids it's their responsibility to educate.

But it appears they'd rather punish kids in districts whose communities are fed up with paying local taxes to fund what is a state funding responsibility. And that, I suppose is what passes as fair.

Sure seems unfair to me.

“We are really trying to say we are trying to help those who can’t help themselves,” Kasich told the Columbus Dispatch. “For those that can help themselves, we need you to step up and help.”

First of all, it's the state whose responsibility it is to provide the funding for education in this state, not local taxpayers. That's what the Ohio Supreme Court ruled four different times. Districts need to ask the state to "step up and help." So that comment was insulting to the Ohio Constitution, not to mention the districts whose communities simply won't pass levies, despite years of trying.

But let's go beyond that and talk about what Kasich means. He's saying, essentially, that if you have the capacity to raise your taxes to pay more for schools than you are, then he's going to cut your state money to punish you. No word if he will then endorse the subsequent levy that will have to go on the ballot to replace that money. But that's the idea. Take money from districts whose taxpayers aren't paying enough and give it to poorer districts whose taxpayers are stepping up more.

The district-by-district runs are not yet out. And what Kasich says and what the runs end up actually doing have diverged quite a bit in recent budgets. But assuming that's the result -- that communities that have contributed more locally will get a bump at the expense of communities that have not, it seems like a push toward equity. And that's good, right? Well, not really.

The effort is meaningless because it's still inadequate.

When you admit that more than 1/2 of all districts will get cut under this plan, even though you're touting a "record" level of funding for schools (a highly dubious claim employing the fuzziest of math), something isn't right. And that something is that the state is not spending enough to properly fund schools.

The fact you are taking money from districts to fund other districts means you don't have enough to fund both. Period. It's inadequate.

And while I love the idea of equity, it doesn't matter if there's an inadequate amount of money to distribute. Here's a demonstration by way of example.

I am taking three of my friends to a $10 movie. I have $36 in my pocket, and no one else has anything. If I equitably distribute the money, we all get $9, but guess what? None of us get into the movie because it's inadequate to meet the ticket price. The only way any of us see the movie is if I decide to inequitably distribute the money so that two or three of us can see it. Maybe it's the two or three who really want to see it, or it's the two or three who help me out the most with babysitting my kids, or it's the two or three who make the least amount of money and can't afford to go without my help. Or I let one friend go without because I know he's got $10 in the console of his car. Whatever the reason, though, I'm pretty well deciding whose worthy of my inadequate amount of money. All of those are perfectly legitimate ways to decide who gets into the movie, but it misses the point.

The essence of true equity is that everyone gets in, regardless of circumstance.

To finish my example, I need to find four more dollars. That's true equity.

What this silly analogy is trying to show that that you simply cannot have true equity without adequacy. This is a concept that Kasich and others simply don't either understand or don't want to face. Because it means that they will have to find a bit more money in the largest state budget of all time for the 1.7 million kids it's their responsibility to educate.

But it appears they'd rather punish kids in districts whose communities are fed up with paying local taxes to fund what is a state funding responsibility. And that, I suppose is what passes as fair.

Sure seems unfair to me.